ESSA’s Evidence Tiers and Potential for Bias

This is the second of a four-part blog posting about changes needed to the legacy of NCLB to make research more useful to school decision-makers. Here we explain how ESSA introduced flexibility and how NCLB-era habits have raised issues about bias. (Read the first one here.)

The tiers of evidence defined in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) give schools and researchers greater flexibility, but are not without controversy. Flexibility creates the opportunity for biased results. The ESSA law, for example, states that studies must statistically control for “selection bias”, recognizing that teachers who “select” to use a program may have other characteristics that give them an advantage and the results for those teachers could be biased upward. As we trace the problem of bias it is useful to go back to the interpretation of ESSA that originated with the NCLB-era approach to research.

When we helped develop the research guidelines for the Software & Information Industry Association, we took a close look at ESSA and how it is often interpreted. Now, as research is evolving with cloud-based educational products that automatically report usage data, it is important to clarify both ESSA’s useful advances and how the four tiers fail to address a critical scientific concept needed for schools to make use of research.

We’ve written elsewhere how the ESSA tiers of evidence form a developmental scale. The four tiers give educators as well as developers of educational materials and products an easier way to start examining effectiveness without making the commitment to the type of scientifically-based research that NCLB once required.

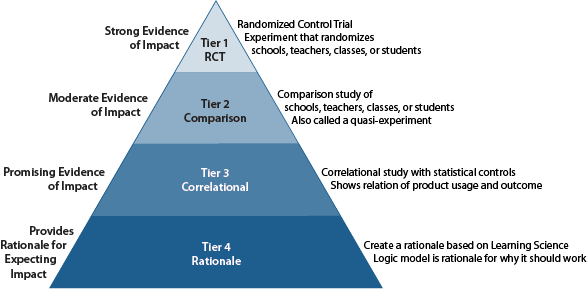

We think of the four tiers of evidence defined in ESSA as a pyramid as shown in this figure.

- RCT. At the apex is Tier 1, defined by ESSA as a randomized control trial (RCT), considered the gold standard in the NCLB era.

- Matched Comparison or “quasi-experiments”. With Tier 2 the WWC also allowed for less rigorous experimental research design, such as matched comparisons or quasi-experiments (QE) where schools, teachers, and students (experimental units) independently chose to engage in the program. QEs are permitted but accepted “with reservations” because without random assignment there is the possibility of “selection bias.” For example, teachers who do well at preparing kids for tests might be more likely to participate in a new program than teachers who don’t excel at test preparation. With an RCT we can expect that such positive traits are equally distributed in the experiment between users and non-users.

- Correlational. Tier 3 is an important and useful addition to evidence, as a weaker but readily achieved method once the developer has a product running in schools. At that point, they have an opportunity to see if critical elements of the program correlate with outcomes of interest. This provides promising evidence, which is useful for both improving the product and giving the schools some indication that it is helping. This evidence suggests that it might be worthwhile to follow up with a tier 2 study for more definitive results.

- Rationale. The base level or Tier 4 is the expectation that any product should have a rationale based on learning science for why it is likely to work. Schools will want this basic rationale for why a program should work before trying it out. Our colleagues at Digital Promise have announced a service in which developers are certified as meeting Tier 4 standards.

Each subsequent tier of evidence (from number 4 to 1) improves what’s considered the “rigor” of the research design. It is important to understand that the hierarchy has nothing to do with whether the results can be generalized from the setting of the study to the district where the decision-maker resides.

While the NCLB-era focus on strong design puts emphasis on the Tier 1 RCT, we see Tiers 2 and 3 as an opportunity for lower cost and faster-turn-around “rapid-cycle evaluations” (RCE.) Tier 1 RCTs have given education research a well-deserved reputation as slow and expensive. It can take one to two years to complete an RCT, with additional time needed for data collection, analysis, and reporting. This extensive work also includes recruiting districts that are willing to participate in the RCT and often puts the cost of the study in the millions of dollars. We have conducted dozens of RCTs following the NCLB-era rules, but advocate less expensive studies in order to get the volume of evidence schools need. In contrast to an RCT, an RCE can use existing data from a school system can be both faster and far less expensive.

There is some controversy about whether schools should use lower-tier evidence, which might be subject to “selection bias.” Randomized control trials are protected from selection bias since users and non-user are assigned randomly, whether they like it or not. It is well known and has been recently pointed out by Robert Slavin that using a matched comparison, a study where teachers chose to participate in the pilot of a product, can result in unmeasured variables, technically “confounders” that affect outcomes. These variables are associated with the qualities that motivate a teacher to pursue pilot studies and their desire to excel in teaching. The comparison group may lack these characteristics that help the self-selected program users succeed. Studies of Tiers 2 and 3 will always have, by definition, unmeasured variables that may act as confounders.

While obviously a concern, there are ways that researchers can statistically control important characteristics associated with selection to use a program. For example, the amount of a teacher’s motivation to use edtech products can be controlled by collecting information from the prior year on the amount of usage by the teacher and students of a full set of products. Past studies looking at the conditions under which there is correspondence between results of RCTs and matched comparison studies that evaluate the impact of a given program have established that it is exactly “focal” variables such as motivation, that are influential confounders. Controlling for a teacher’s demonstrated motivation and students’ incoming achievement may go very far in adjusting away bias. We suggest this in a design memo for a study now being undertaken. This statistical control meets the ESSA requirement for Tiers 2 and 3.

We have a more radical proposal for controlling all kinds of bias that we address in the next posting in this series.