Can We Measure the Measures of Teaching Effectiveness?

Teacher evaluation has become the hot topic in education. State and local agencies are quickly implementing new programs spurred by federal initiatives and evidence that teacher effectiveness is a major contributor to student growth. The Chicago teachers’ strike brought out the deep divisions over the issue of evaluations. There, the focus was on the use of student achievement gains, or value-added. But the other side of evaluation—systematic classroom observations by administrators—is also raising interest. Teaching is a very complex skill, and the development of frameworks for describing and measuring its interlocking elements is an area of active and pressing research. The movement toward using observations as part of teacher evaluation is not without controversy. A recent OpEd in Education Week by Mike Schmoker criticizes the rapid implementation of what he considers overly complex evaluation templates “without any solid evidence that it promotes better teaching.”

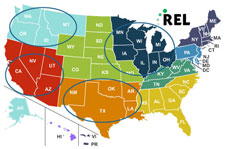

There are researchers engaged in the careful study of evaluation systems, including the combination of value-added and observations. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has funded a large team of researchers through its Measures of Effective Teaching (MET) project, which has already produced an array of reports for both academic and practitioner audiences (with more to come). But research can be ponderous, especially when the question is whether such systems can impact teacher effectiveness. A year ago, the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) awarded an $18 million contract to AIR to conduct a randomized experiment to measure the impact of a teacher and leader evaluation system on student achievement, classroom practices, and teacher and principal mobility. The experiment is scheduled to start this school year and results will likely start appearing by 2015. However, at the current rate of implementation by education agencies, most programs will be in full swing by then.

Empirical Education is currently involved in teacher evaluation through Observation Engine: our web-based tool that helps administrators make more reliable observations. See our story about our work with Tulsa Public Schools. This tool, along with our R&D on protocol validation, was initiated as part of the MET project. In our view, the complexity and time-consuming aspects of many of the observation systems that Schmoker criticizes arise from their intended use as supports for professional development. The initial motivation for developing observation frameworks was to provide better feedback and professional development for teachers. Their complexity is driven by the goal of providing detailed, specific feedback. Such systems can become cumbersome when applied to the goal of providing a single score for every teacher representing teaching quality that can be used administratively, for example, for personnel decisions. We suspect that a more streamlined and less labor-intensive evaluation approach could be used to identify the teachers in need of coaching and professional development. That subset of teachers would then receive the more resource-intensive evaluation and training services such as complex, detailed scales, interviews, and coaching sessions.

The other question Schmoker raises is: do these evaluation systems promote better teaching? While waiting for the IES study to be reported, some things can be done. First, look at correlations of the components of the observation rubrics with other measures of teaching such as value-added to student achievement (VAM) scores or student surveys. The idea is to see whether the behaviors valued and promoted by the rubrics are associated with improved achievement. The videos and data collected by the MET project are the basis for tools to do this (see earlier story on our Validation Engine.) But school systems can conduct the same analysis using their own student and teacher data. Second, use quasi-experimental methods to look at the changes in achievement related to the system’s local implementation of evaluation systems. In both cases, many school systems are already collecting very detailed data that can be used to test the validity and effectiveness of their locally adopted approaches.