There has been a powerful misconception driving policy in education. It’s a case where theory was inappropriately applied to practice. The misconception has had unintended consequences. It is helping to lead large numbers of parents to opt out of testing and could very well weaken the case in Congress for accountability as ESEA is reauthorized.

The idea that we can use student test scores as one of the measures in evaluating teachers came into vogue with Race to the Top. As a result of that and related federal policies, 38 states now include measures of student growth in teacher evaluations.

This was a conceptual advance over the NCLB definition of teacher quality in terms of preparation and experience. The focus on test scores was also a brilliant political move. The simple qualification for funding from Race to the Top—a linkage between teacher and student data—moved state legislatures to adopt policies calling for more rigorous teacher evaluations even without funding states to implement the policies. The simplicity of pointing to student achievement as the benchmark for evaluating teachers seemed incontrovertible.

It also had a scientific pedigree. Solid work had been accomplished by economists developing value-added modeling (VAM) to estimate a teacher’s contribution to student achievement. Hanushek et al.’s analysis is often cited as the basis for the now widely accepted view that teachers make the single largest contribution to student growth. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation invested heavily in its Measures of Effective Teaching (MET) project, which put the econometric calculation of teachers’ contribution to student achievement at the center of multiple measures.

The academic debates around VAM remain intense concerning the most productive statistical specification and evidence for causal inferences. Perhaps the most exciting area of research is in analyses of longitudinal datasets showing that students who have teachers with high VAM scores continue to benefit even into adulthood and career—not so much in their test scores as in their higher earnings, lower likelihood of having children as teenagers, and other results. With so much solid scientific work going on, what is the problem with applying theory to practice? While work on VAMs has provided important findings and productive research techniques, there are four important problems in applying these scientifically-based techniques to teacher evaluation.

First, and this is the thing that should have been obvious from the start, most teachers teach in grades or subjects where no standardized tests are given. If you’re conducting research, there is a wealth of data for math and reading in grades three through eight. However, if you’re a middle-school principal and there are standardized tests for only 20% of your teachers, you will have a problem using test scores for evaluation.

Nevertheless, federal policy required states—in order to receive a waiver from some of the requirements of NCLB—to institute teacher evaluation systems that use student growth as a major factor. To fill the gap in test scores, a few districts purchased or developed tests for every subject taught. A more wide-spread practice is the use of Student Learning Objectives (SLOs). Unfortunately, while they may provide an excellent process for reflection and goal setting between the principal and teacher, they lack the psychometric properties of VAMs, which allow administrators to objectively rank a teacher in relation to other teachers in the district. As the Mathematica team observed, “SLOs are designed to vary not only by grade and subject but also across teachers within a grade and subject.” By contrast, academic research on VAM gave educators and policy makers the impression that a single measure of student growth could be used for teacher evaluation across grades and subjects. It was a misconception unfortunately promoted by many VAM researchers who may have been unaware that the technique could only be applied to a small portion of teachers.

There are several additional reasons that test scores are not useful for teacher evaluation.

The second reason is that VAMs or other measures of student growth don’t provide any indication as to how a teacher can improve. If the purpose of teacher evaluation is to inform personnel decisions such as terminations, salary increases, or bonuses, then, at least for reading and math teachers, VAM scores would be useful. But we are seeing a widespread orientation toward using evaluations to inform professional development. Other kinds of measures, most obviously classroom observations conducted by a mentor or administrator—combined with feedback and guidance—provide a more direct mapping to where the teacher needs to improve. The observer-teacher interactions within an established framework also provide an appropriate managerial discretion in translating the evaluation into personnel decisions. Observation frameworks not only break the observation into specific aspects of practice but provide a rubric for scoring in four or five defined levels. A teacher can view the training materials used to calibrate evaluators to see what the next level looks like. VAM scores are opaque in contrast.

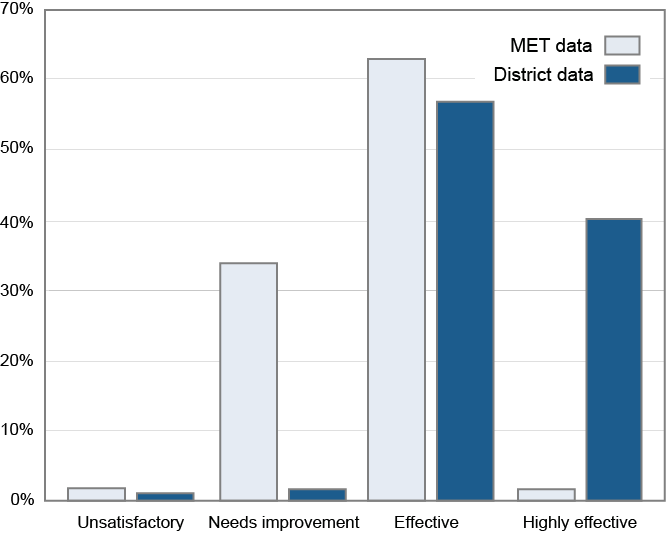

Third, test scores are associated with a narrow range of classroom practice. My colleague, Val Lazarev, and I found an interesting result from a factor analysis of the data collected in the MET project. MET collected classroom videos from thousands of teachers, which were then coded using a number of frameworks. The students were tested in reading and/or math using an assessment that was more focused on problem-solving and constructive items than is found in the usual state test. Our analysis showed that a teacher’s VAM score is more closely associated with the framework elements related to classroom and behavior management (i.e., keeping order in the classroom) than the more refined aspects of dialog with students. Keeping the classroom under control is a fundamental ability associated with good teaching but does not completely encompass what evaluators are looking for. Test scores, as the benchmark measure for effective teaching, may not be capturing many important elements.

Fourth, achievement test scores (and associated VAMs) are calculated based on what teachers can accomplish with respect to improving test scores from the time students appear in their classes in the fall to when they take the standardized test in the spring. If you ask people about their most influential teacher, they talk about being inspired to take up a particular career or about keeping them in school. These are results that are revealed in following years or even decades. A teacher who gets a student to start seeing math in a new way may not get immediate results on the spring test but may get the student to enroll in a more challenging course the next year. A teacher who makes a student feel at home in class may be an important part of the student not dropping out two years later. Whether or not teachers can cause these results is speculative. But the characteristics of warm, engaging, and inspiring teaching can be observed. We now have analytic tools and longitudinal datasets that can begin to reveal the association between being in a teacher’s class and the probability of a student graduating, getting into college, and pursuing a productive career. With records of systematic classroom observations, we may be able, in the future, to associate teaching practices with benchmarks that are more meaningful than the spring test score.

The policy-makers’ dream of an algorithm for translating test scores into teacher salary levels is a fallacy. Even the weaker provisions such as the vague requirement that student growth must be an important element among multiple measures in teacher evaluations has led to a profusion of methods of questionable utility for setting individual goals for teachers. But the insistence on using annual student achievement as the benchmark has led to more serious, perhaps unintended, consequences.

Teacher unions have had good reason to object to using test scores for evaluations. Teacher opposition to this misuse of test scores has reinforced a negative perception of tests as something that teachers oppose in general. The introduction of the new Common Core tests might have been welcomed by the teaching profession as a stronger alignment of the test with the widely shared belief about what is important for students to learn. But the change was opposed by the profession largely because it would be unfair to evaluate teachers on the basis of a test they had no experience preparing students for. Reducing the teaching profession’s opposition to testing may help reduce the clamor of the opt-out movement and keep the schools on the path of continuous improvement of student assessment.

We can return to recognizing that testing has value for teachers as formative assessment. And for the larger community it has value as assurance that schools and districts are maintaining standards, and most importantly, in considering the reauthorization of NCLB, not failing to educate subgroups of students who have the most need.

A final note. For purposes of program and policy evaluation, for understanding the elements of effective teaching, and for longitudinal tracking of the effect on students of school experiences, standardized testing is essential. Research on value-added modeling must continue and expand beyond tests to measure the effect of teachers on preparing students for “college and career”. Removing individual teacher evaluation from the equation will be a positive step toward having the data needed for evidence-based decisions.

An abbreviated version of this blog post can be found on Real Clear Education.